One of the new cases for the exhibition turnover is dedicated to the fine binding collection of James Thielman, a man I can best describe as two whole hoots. Thielman was a bookdealer who began collecting and commissioning fine bindings of his own books in 1977 after he retired from being an antiquarian bookdealer. He wrote first to Elizabeth Greenhill, a well-respected English bookbinder, and she delivered the agreed-upon binding in person at the International Exhibition of Bookbinding in San Francisco in 1978. Thielman was so pleased that he immediately commissioned a second binding from her, Bacchae by Euripides, which we placed on view last week.

And so began a 15-year period in which James Thielman commissioned or purchased nearly 80 finely bound books, paying anywhere from $700 to $10,000 for each binding. He wrote to binders in the United States and Europe, often asking them to pick between a few books from his personal collection to bind, then sending along the chosen volume. The new binding replaced the old, which Thielman also retained where possible.

The resulting collection is not entirely unlike a collection of illuminated manuscripts; both art forms treat the text object as a vehicle for artistic embellishment, visualization, and celebration. As Thielman wrote in a June 1988 letter to Sylvia Rennie, a Swiss-English-Wisconsinite bookbinder, “The only reason a person has a fine binding on a book is to make it more attractive—not to make it something it isn't.”

To prepare our descriptions for the bindings we’re exhibiting, I read through Thielman’s correspondence with the bookbinders of his fine bindings. I fear I may never again have such a raucous time reading through someone else’s letters. Thielman was highly opinionated and occasionally sharp-tongued, always forthcoming and precise (he attached receipts to his letters for binders to indicate they had received his books in fine condition, then return for Thielmans’s records).

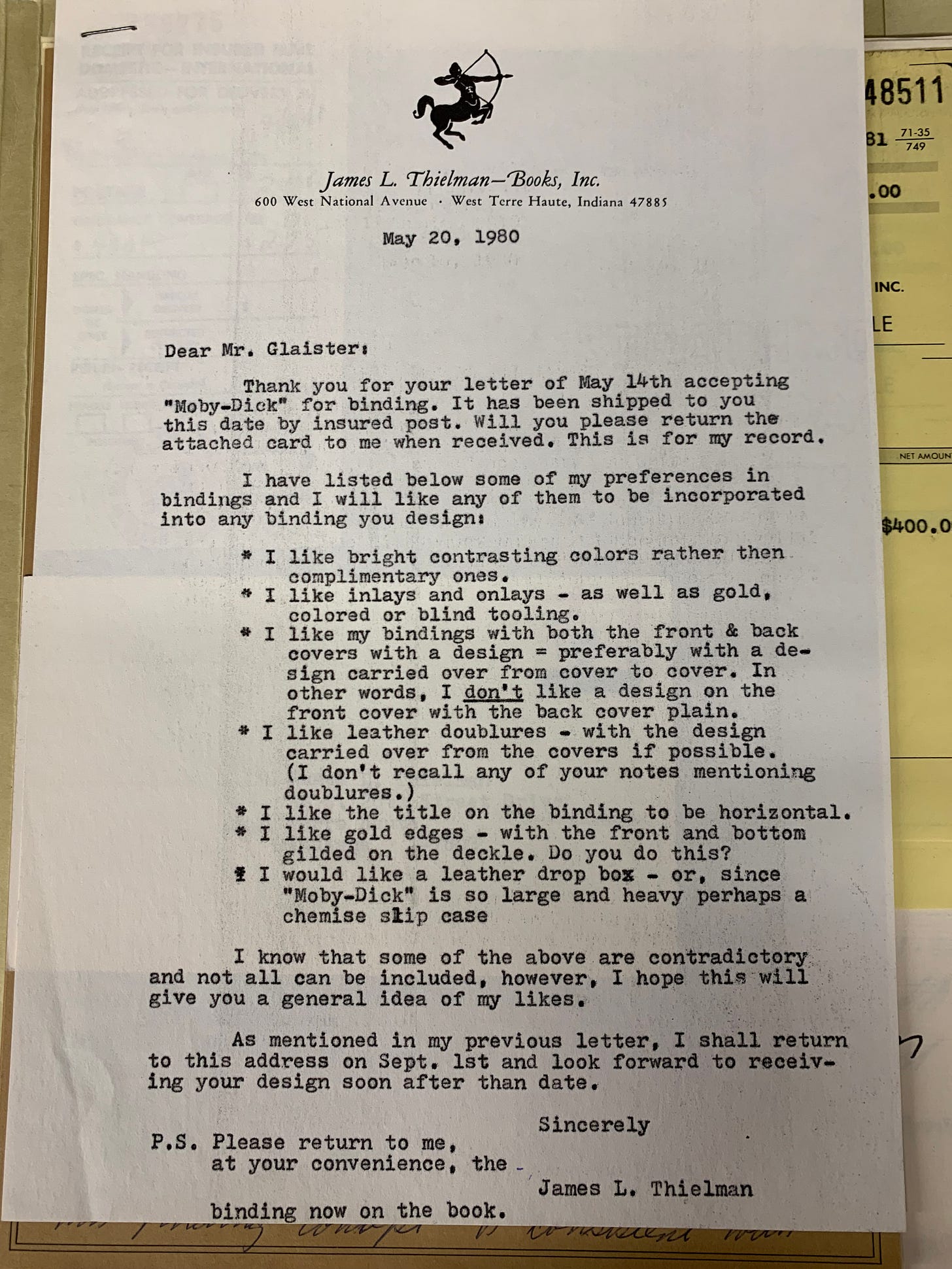

Take this letter from May 20, 1980, which Thielman wrote to Donald Glaister regarding his first commission, Moby Dick (Thielman would end up with six fine bindings of Moby Dick. Big whale guy):

Although this list seems like a tall order, barely softened by Thielman’s admission, “I know that some of the above are contradictory and not all can be included,” it actually demonstrates that he had mellowed a bit. In 1978, he sent a stricter list to Susan Spring Wilson, concluding “if there are any contradictions, you will just have to sort them out.”

Thielman was as patient as he was exacting, often expecting a one- or two-year wait time for his bindings. The limits of that patience occassionally revealed themselves in veiled, underhanded insults. In his early correspondence with Glaister, Thielman wrote, “I also like your promptness. I have found in dealing with binders they are not always as prompt as they promise to be.”

Yet such tardiness was inescapable in this collecting niche. In January 1983, after waiting two years for two bindings of Moby Dick (one for himself, one for his son Larry) to arrive from the English binder James Brockman, Thielman writes: “Was the design sent and could it have gone astray in the mail? I know that binders never seem to have enough time and if this is the case, it is O.K.”

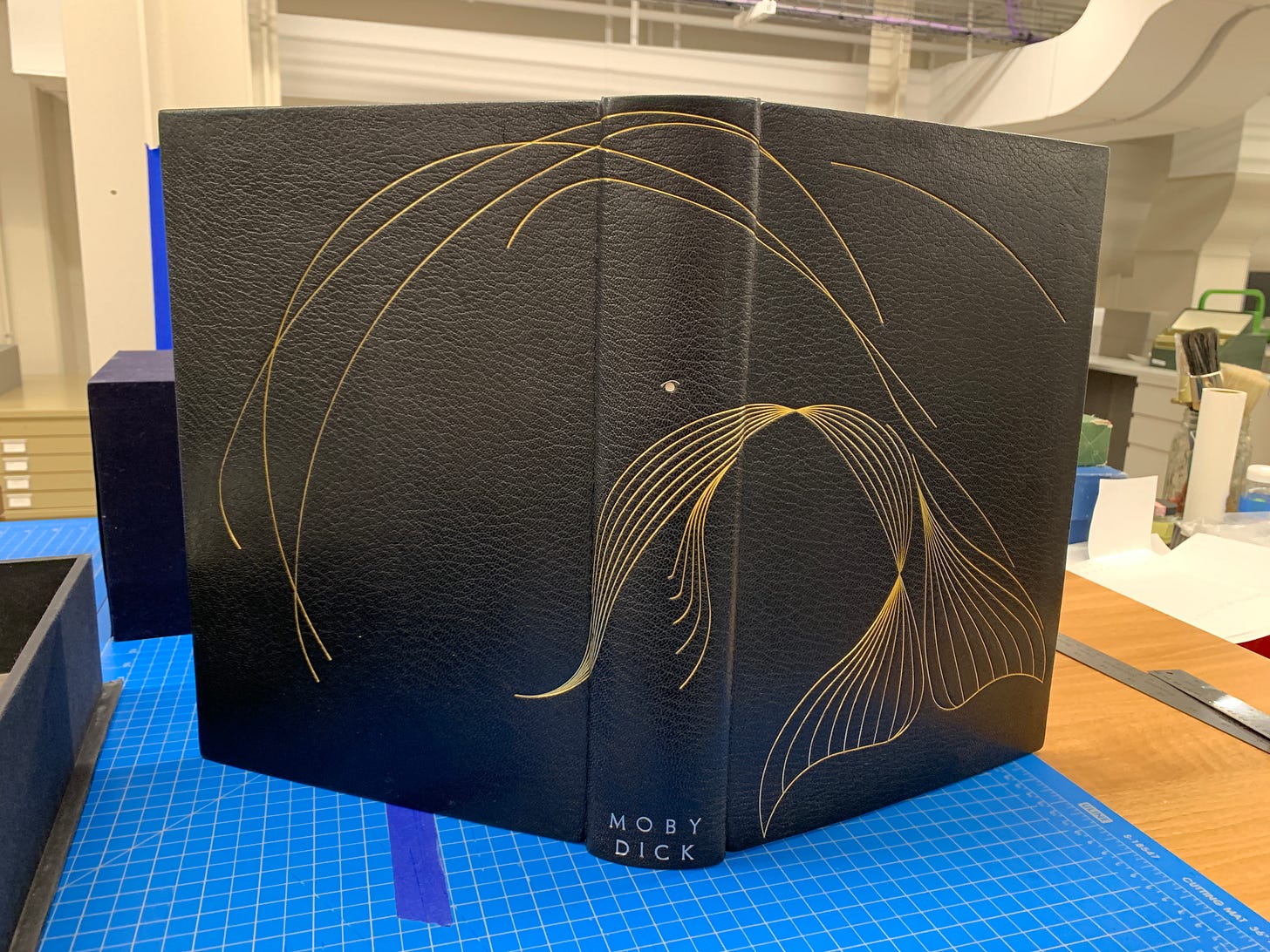

Finally, after three years of delays due to Brockman's artist’s residence at the Welsh Gregynog Press (which has its own curious history), then because of a special rush order for a gift book for President Ronald Reagan's visit to Ireland, Thielman happily receives his Moby Dick on August 24, 1984.

Despite accounting for this tardiness in his finances and correspondence, Thielman remained especially sore with Continental bookbinders, who he unforgivingly lamented as uncommunicative and slow, even though his 1988 orders were delayed by a mail worker strike (where’s the solidarity, man?). After receiving a book for which he waited five agonizing years, he confided to Rennie, “[The binder] may have put a lot of thought into it—but it seems to me the actual work was very little.” Brutal.

There were many personalities at play in this collection, not just Thielman’s, and the bookbinders were not short on snark in reply. One dealer wrote a three-page treatise on why he priced his bindings as he did, arguing for fair compensation to take care of his family during the laborious, time-consuming process of designing and executing the bindings. Thielman replied wryly: “I have no rebuttal to your letter...My only answer is that I am not financially in a position to spend 6000 on a binding. It is that simple. A retired person with a fixed income has to set his priorities too.” (He ended up spending $6,200 on the binding, which happened to be yet another Moby Dick.)

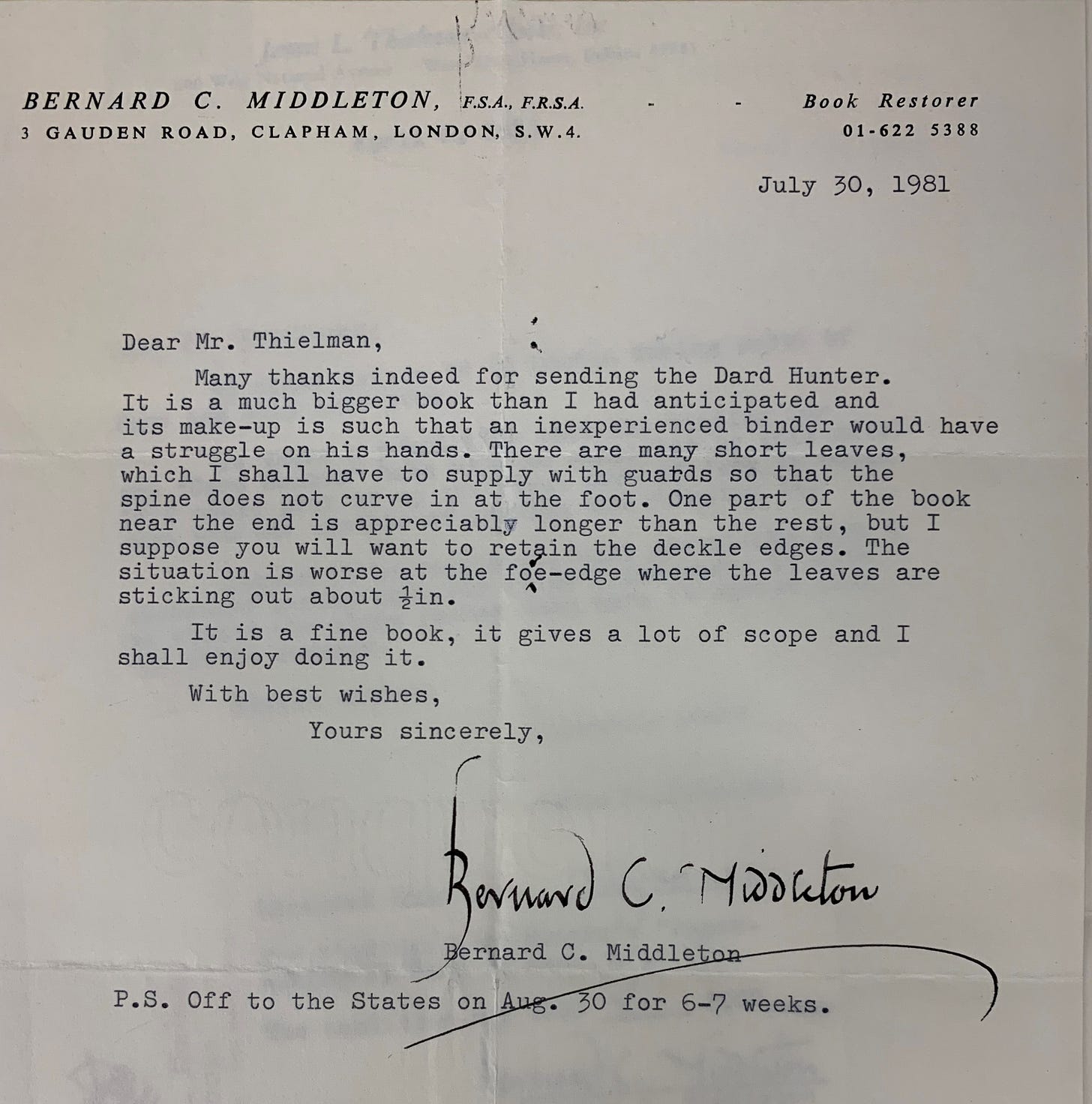

Another of my favorite letters was from Bernard Middleton. Read what he has to say about the volume Thielman sent him:

What a verbose way of saying “This book sucks. I love it.”

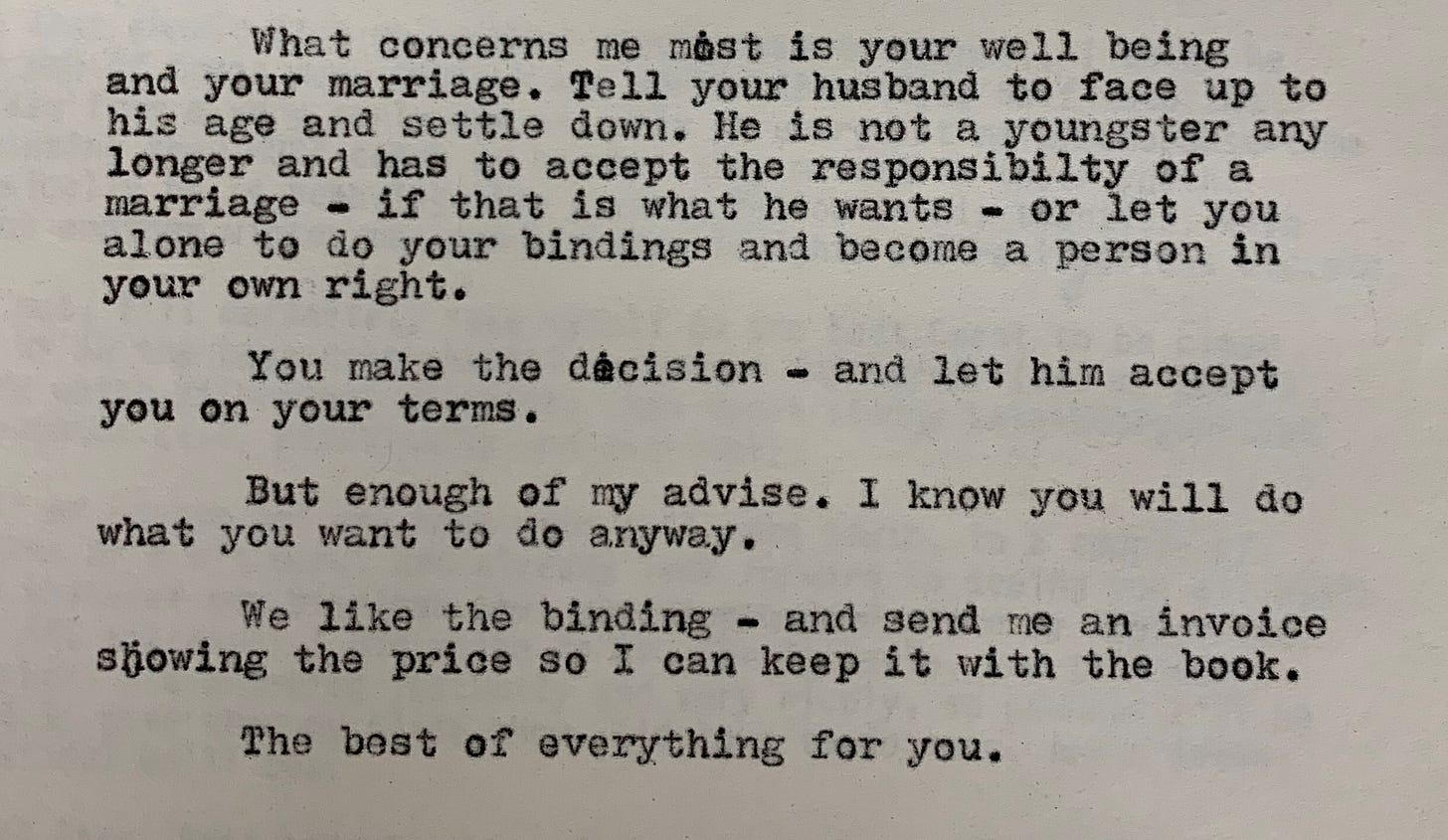

Thielman’s letters also document enduring professional relationships and fierce friendships with artists whose work he deeply admired and whose companionship he clearly valued. Those relationships were clearest with Donald Glaister and Sylvia Rennie, with whom Thielman maintained frequent correspondence. While Glaister’s decade-long correspondence made for a hefty folder, Rennie’s chatty letters comprised three thick files, running the gamut from commissions to exhibition announcements to notices on her house moves. In 1986, Thielman, ever the thoughtful correspondent, advised Rennie on how to manage her absentee husband:

Each binding in Thielman’s collection manifests these conversations and relationships, whether through the back-and-forth of design ideas and material samples, Thielman’s increasing trust to let a binder run amok, or their personal confidences and small kindnesses (in each of his letters to Brockman, Thielman sent US stamps for Brockman’s sons, who were collecting stamps at the time. By the time Brockman finished Moby Dick, his sons had moved on to soccer).

Working between these two facets of Thielman’s collection—the material products born from immaterial relationships—is my favorite part of working in a special collections library. A lot of my work involves tracking down one-sided accounts of relationships or production history; this was a rare instance of having everything in one place due to one man’s meticulous documentation of his collection and the archival organization of those records. The hardest part was over, and I could reap the reward of reading a person through their collection and correspondence.

Thielman’s bindings alone speak volumes: he loved color, gilt, and patterns. He loved bindings that built on a text’s meaning. He loved boldness and striking designs, even as he stuck to the plain Jane basicness of a codex, with little fascination for the avant-garde three-dimensional book arts that emerged in this period. He loved binders with a vision, and he respected that vision, even when it took time to grow on him.

His correspondence tells the richness of the friendships developed alongside and within these objects. These books are peopled at every turn. Illustratively, for his 50th binding, Thielman wrote to Elizabeth Greenhill once again, asking her to design a fine binding for his inscribed copy of her career retrospective catalogue, which had been compiled to celebrate her retirement in 1984. He wrote, “I feel it only appropriate that you design the binding, as you were the one to begin it all.”

Housekeeping and birdseeking

house

What I read this week: Island by Siri Ranva Hjelm Jacobsen, translated by Caroline Wright, and Filthy Animals by Brandon Taylor

What I’m currently reading: The Night Watchman by Louise Erdrich

A reminder to send me your questions via email or comments! About anything, though preferably somewhat related to the newsletter.

bird

More later.

1) I am SO curious to know whether the skeletons of those birds just look like normal skeletons 2) This is making me want to get my favorite books bound but I don't think I could ever afford it