I have a handful of hours per week when I am not in class or clocked in, but no matter how rundown or tired I am, I always feel better after I’ve worked with books in the Reading Room at the Lilly. We’ve spent the last few weeks on very complex topics of representation and organization; before I finish that series, I figured I’d treat us all to a well-earned book break, facilitated by my second assignment for Rare Book Librarianship.

When I last wrote about Rare Book Librarianship, I reflected on the different kinds of work rare book librarians do and how they commit to making good change. You might recall one of the primary responsibilities I discussed as “stewardship,” or the material and intellectual development & interpretation of our collections; this assignment encourages us to practice that interpretation of materials through telling the story of a single object in the Lilly Library.

The object I picked called to me from the stacks, as some of our best bookish friends tend to do. On a visit to the upper floors of the Lilly Library, a large, deep blue box marked with a silver circle winked up at me from the bottom row of shelves. The text on the side of the box read Maestri rilegatori; I understand Italian as Spanish in italics, so I parsed “maestri” as “master, but “rilegatori” was a mystery.

Many happy hours later (and admonitions from my classmates telling me to just turn this project in), here’s what I learned:

L'Infinito: text & translation

That big blue box is a double-slotted slip case, or a box with divided sections to house two volumes: L’Infinito and Maestri rilegatori. The former is a compilation of 74 translations of 19th-century Italian philosopher Giacomo Leopardi’s poem “L’Infinito” (“The Infinite”). The latter is a catalog of 917 bespoke bindings designed by fine bookbinders from 38 countries to house those “L’Infinito” translations, commissioned in 1998 for the 200th anniversary celebration of Leopardi’s birth.1

In his poem (which I recommend reading, at first I was pretty meh about it but it grew on me), Leopardi meditates on how thinking about the infinity of the universe is a deeply spiritual, if not disquieting, experience, concluding that he is content to founder in the unfathomable enormity of that sea of thought. He strikes some resonant themes: the majesty of our natural world, the cycles of life and death, the all-encompassing feeling of tranquility and contentment. The full title of this volume of 74 translations is L’Infinito: in tutte le lingue che l’hanno Saputo pronunciare, or “The Infinite: in all the languages that have been able to pronounce it,” gesturing to how widespread the pronunciation—rather, the expression—of Leopardi’s poem is given its resonance across languages and cultures.

“Widespread” is a generous characterization, as alongside nearly every European language (which is, admittedly, a lot), the volume includes translations in Sanskrit, Japanese, Chinese, and two Mozambique dialects. Not exactly a representative sampling of global languages, but turning the pages is a brisk backpacking trip through the European branch of the Indo-European language tree.

If nothing else, gathering all of these translations in one volume demonstrates the enduring allure of revisiting Leopardi’s text across time and space. Take his final line, for example:

“Infinità s’annega il pensier mio: / E ’l naufragar m ‘è dolce in questo mare.”

And observe the changes in three of the seven successive English translations:

“My thought immensity is drowned; / And sweet to me is shipwreck on this sea.” Frederick Townsend, 1887

“In this immensity my thought sinks drowned: / And sweet it seems to shipwreck in this sea.” R.C. Trevelyan, 1941

“In that immensity my thought is drowned: / And sweet to me the foundering in that sea.” John Heath-Stubbs, 1966

The intricacies of translation often go underacknowledged: translation is a painting of time, culture, connotation, and consequence that requires inhabiting an author’s voice as well as the public consciousness of two (or more) cultures.2 Seeing those paintings side-by-side demonstrates how translation is an art, not simply inputting find & replace between two languages.

From a book historical perspective, the transit of texts often relied on the translation skills of printers or book commissioners. William Caxton, who brought printing to England, first worked as a printer in Flanders where he translated French texts to English until he realized there wasn’t a huge market for English texts on the Continent. He then moved back to London, where he continued to translate texts from the Continent for English readership. Without translators close to the printing process, readers simply had to know other languages to read texts in their original composition. Gathering these translations in one volume is like one big arrival after “L’Infinito”’s long travels.

For special collections librarians, a widely-disseminated text poses fun (and laborious) prospects of bringing those versions together. To visualize that transit, we’d have to track down all the volumes where these translations appear and lay them out on a classroom table or in an exhibition case or in a catalog. The commissioners of this volume did all that legwork for us by bringing these 74 translations together, capturing the transit of Leopardi’s “L’Infinito” across time and space.

L'Infinito: textiles & translation

The commissioners of these volumes weren’t just interested in gathering existing interpretations of Leopardi’s text. They also wanted to generate new ones. To illustrate L’Infinito’s reach, they invited over 6,000 fine bookbinders across the globe to design bespoke bindings. They received 917 yesses and shipped off the text to 38 countries, receiving fully bound books in return. This practice of binding a text far from where it was printed parallels early-modern book practices: Shipping bound books was much heavier and therefore much more expensive than shipping unbound textblocks, so printers sold text blocks wholesale to booksellers. Booksellers would then bind the books themselves, or buyers would commission bespoke bindings to their tastes.

All 917 bindings are catalogued in the behemoth second book, Maestri rilegatori¸ meaning “Master bookbinders,” a profound aggregation of style and technique in a single volume. The catalog captures in print the celebratory exhibition of L’Infinito and its various houses, documenting it for the foreseeable future—the foreseeable infinity that Leopardi meditates on in his poem.

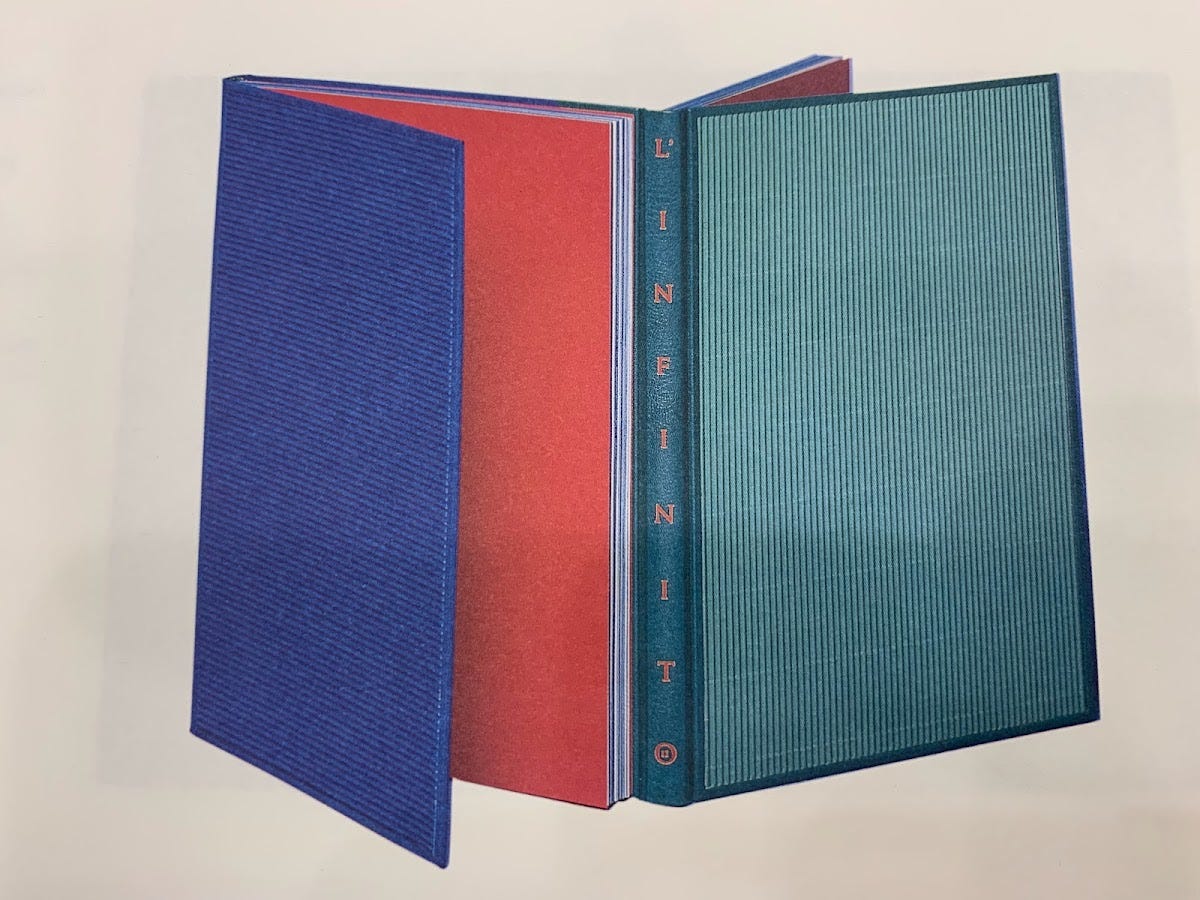

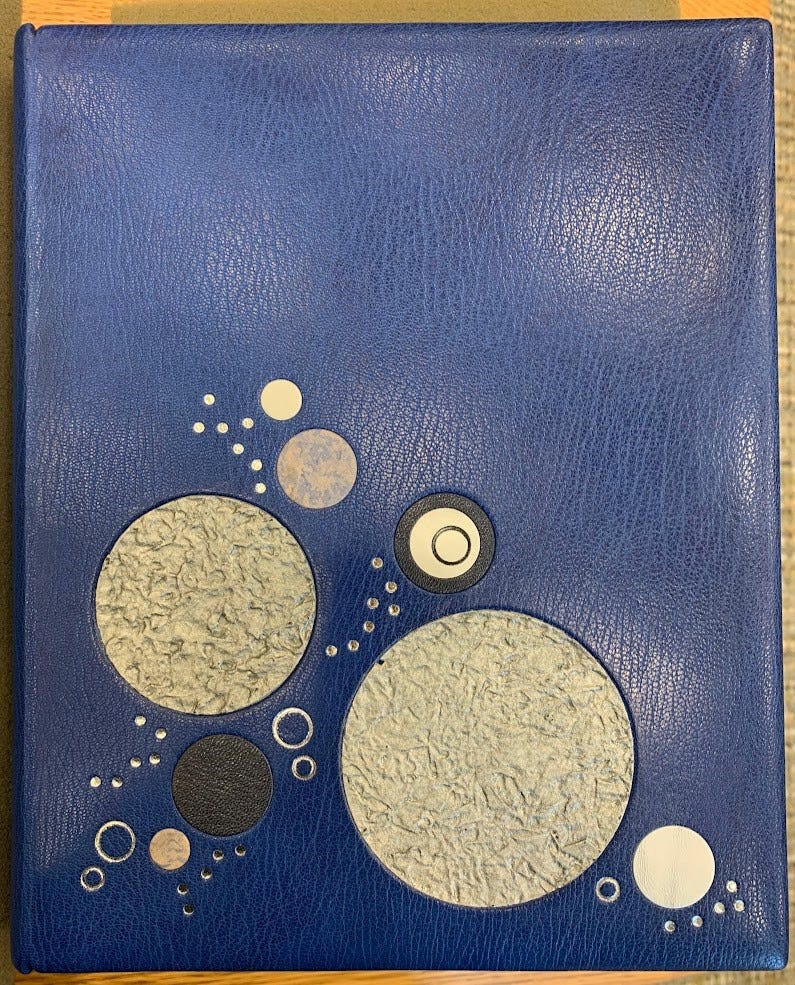

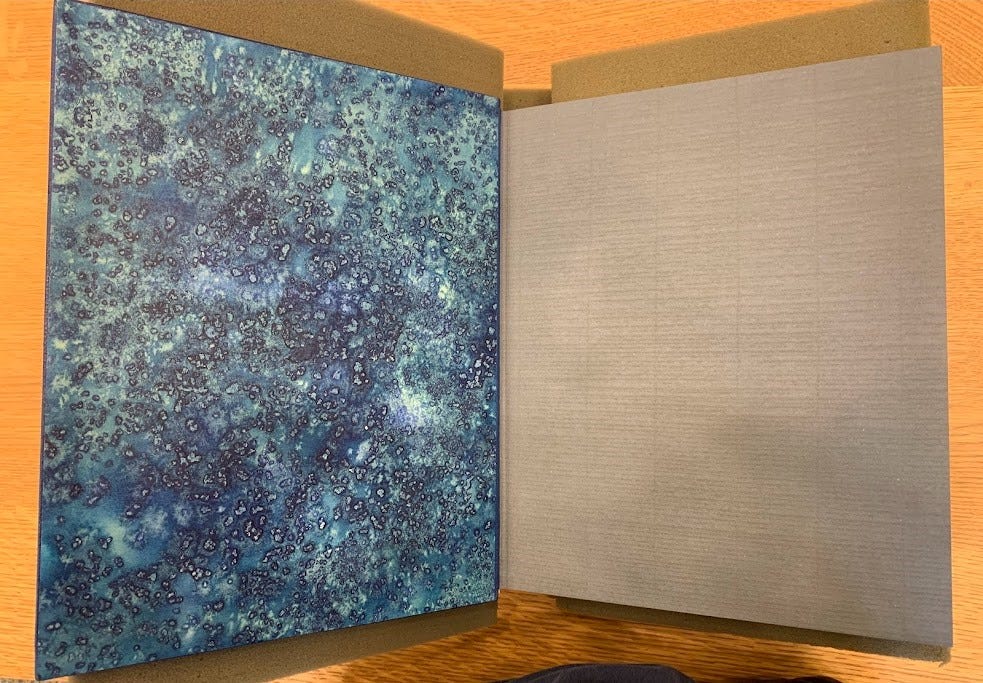

The copies I worked with were bound by a British bookbinder, Stephen Conway, in early-dawn blue morocco. Conway’s binding for Maestri rilegatori is decorated with silver tooling, black morocco and blue and silver calf circular insets, with gray and blue paper spine label printed in blue ink, blue and turquoise speckled pastedowns, and gray hand-made endpapers.

Conway’s decoration of the Maestri binding conjures a full moon and her reflection rippling in ocean waves, evoking the final line of Leopardi’s thoughts foundering in a dark, roiling sea—

“In this immensity my thought sinks drowned: / And sweet it seems to shipwreck in this sea.” R.C. Trevelyan, 1941

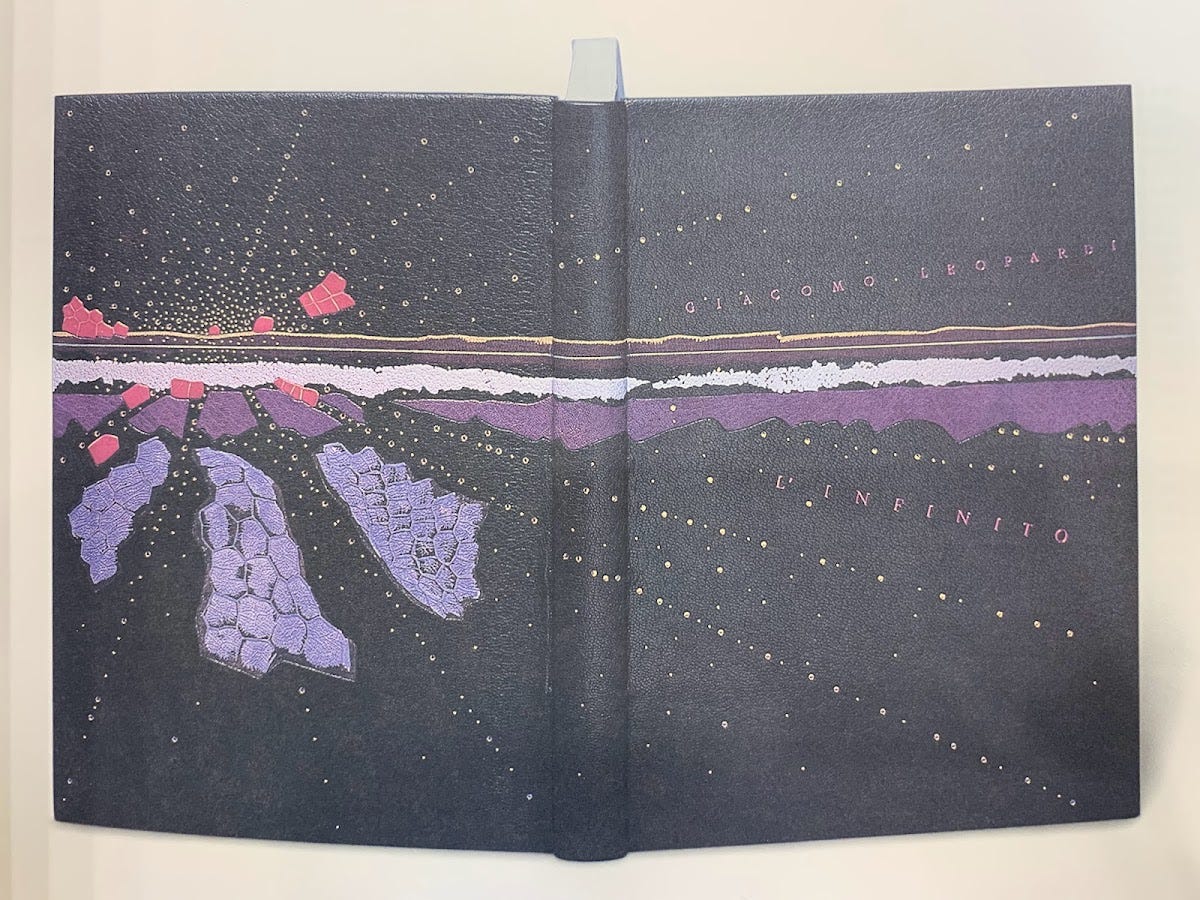

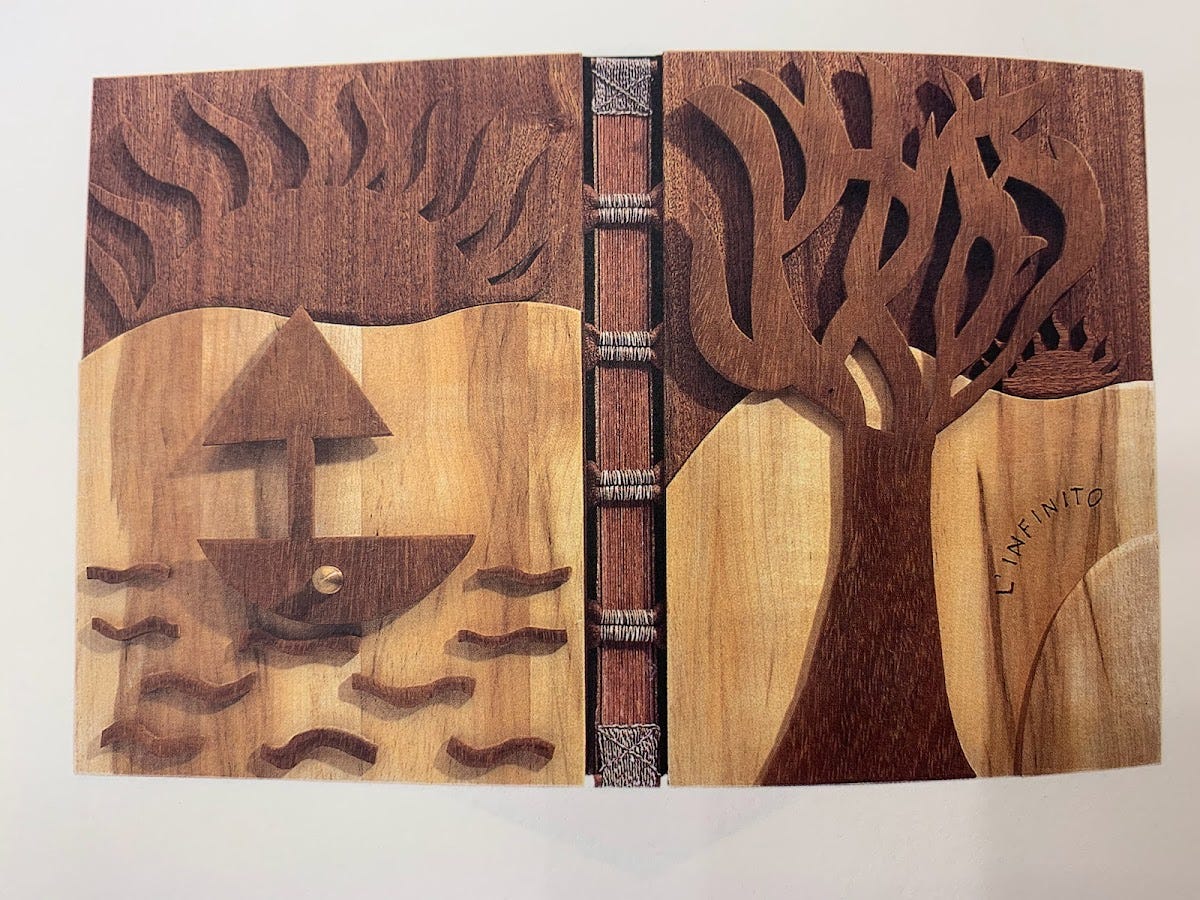

The binding, accented with these silver dollops of sky, literally bookends a similarly infinite sea of interpretations of Leopardi’s text. Inside Maestri rilegatori, the vast array of unique bindings capture the vast array of interpretations of this enduring text: recurring themes include nature, trees, water, planets, astronomy, geometric shapes and patterns, landscapes, leaves, birds (birds!), wind, and circles. The binders used leather, plexiglass, wood, cloth, metal, strings, embroidery, paintings, papers, and pretty much every material you can think of to translate the text into visual, tactile, and textual forms.

Nicholas Pickwoad, an expert in European bookbinding methods, can locate a binding to time, region, and sometimes shop based on the style of knots and arrangement of strings in a binding—the technique was that specific. The bindings in the Maestri catalog are similarly telling of their respective binders’ techniques, as demonstrated with the kinds of materials they employed to express their interpretation of “L’Infinito.”

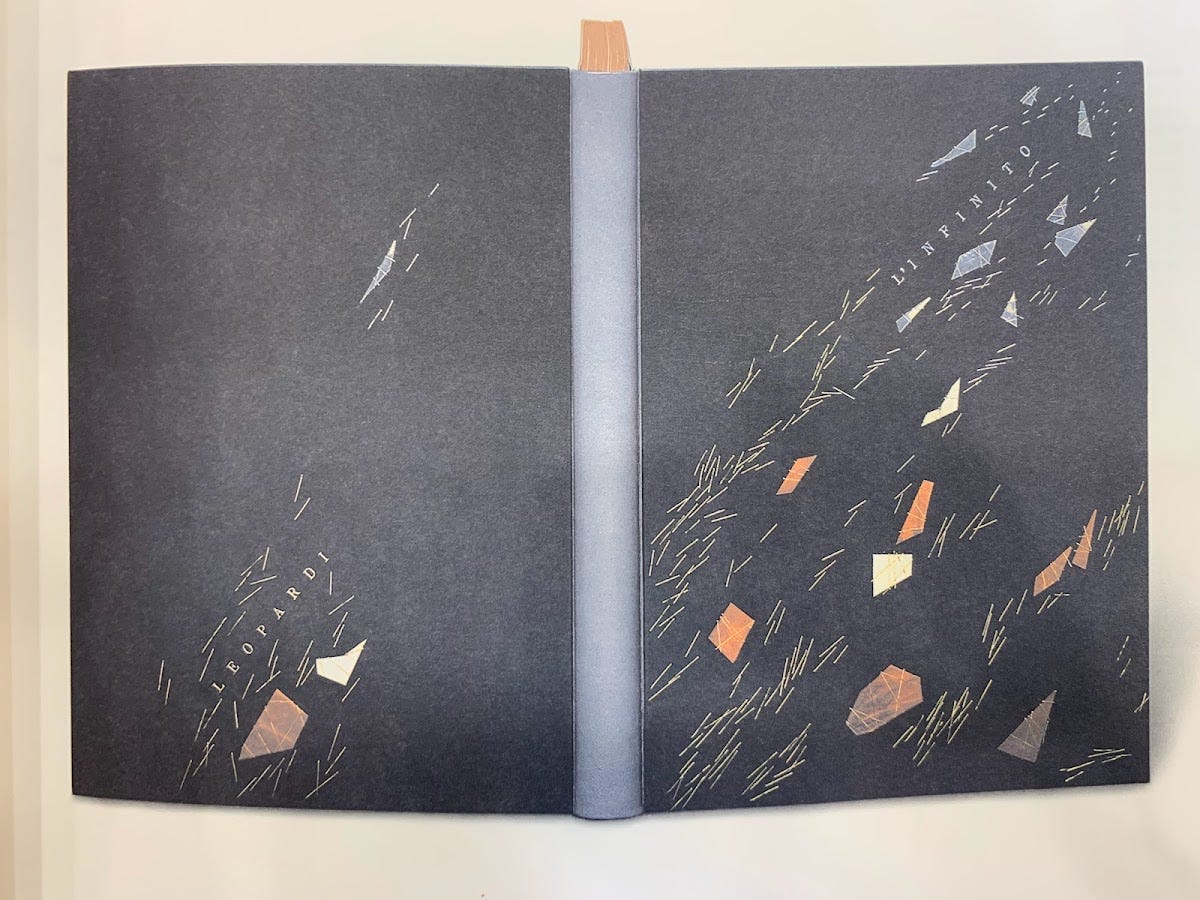

Consider this binding from De JongTessy, Handboekbinderij Tess in the Netherlands. Tessy is a mechanical bookbinder and freelance restorer who hopes (in 1998, at least) to use bookbinding as occupational therapy in their future OT practice. You can see the emphasis on metalworking:

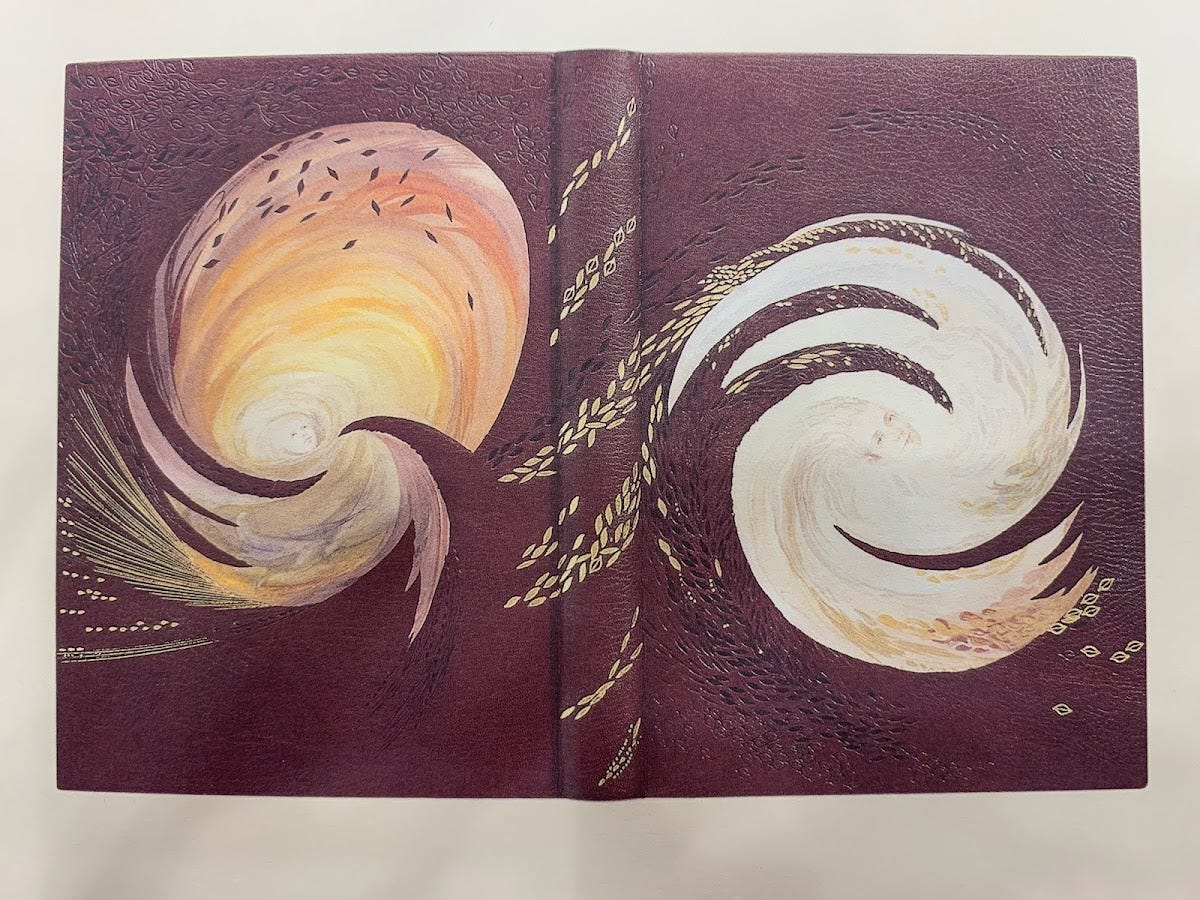

Here are some of my other favorites:

the infinite possibilities of transit & translation

Like ocean waves and seasons and all the other stuff that soothes our hearts, these two volumes materialize a cycle of gathering and disseminating:

the wide-spread dissemination of Leopardi’s poem comes home to roost with these 74 translations in one volume;

the publishers issued nearly one thousand copies of that compilation to fine bookbinders across the globe;

the bookbinders returned the text, newly housed in bespoke bindings of any fathomable material to the celebratory exhibition and evaluation committee;

and finally, the bound volumes were redistributed to binders and bookdealers, eventually finding their way into personal or institutional collections.

Tracking the physical criss-crossing of text and tome parallels the criss-crossing of textual and visual translation. Though these objects are both quite young—commissioned and published in 1997 and 1998—they have already lived multiple cycles of arrival and departure from various bookish homes. Each arrival and departure is an inflection point, a moment of change to consider what (and who) happened to the book and why.

Rare book practitioners are increasingly interested in understanding how people read and respond to texts (a little something called “reception theory”), an elusive field of study that’s very difficult to track. There’s no systematic way to find and analyze marginalia or the public response to works. To have a single catalog of nearly 1000 visual expressions of 74 translations of a text is a bounty in many ways. Maestri rilegatori centralizes many streams of thought into two volumes, a gathering of interpretation and translation that many rare book practitioners could only dream of. In our classrooms and exhibitions, we often curate works that we think speak to one another; these two volumes are many conversations all at once.

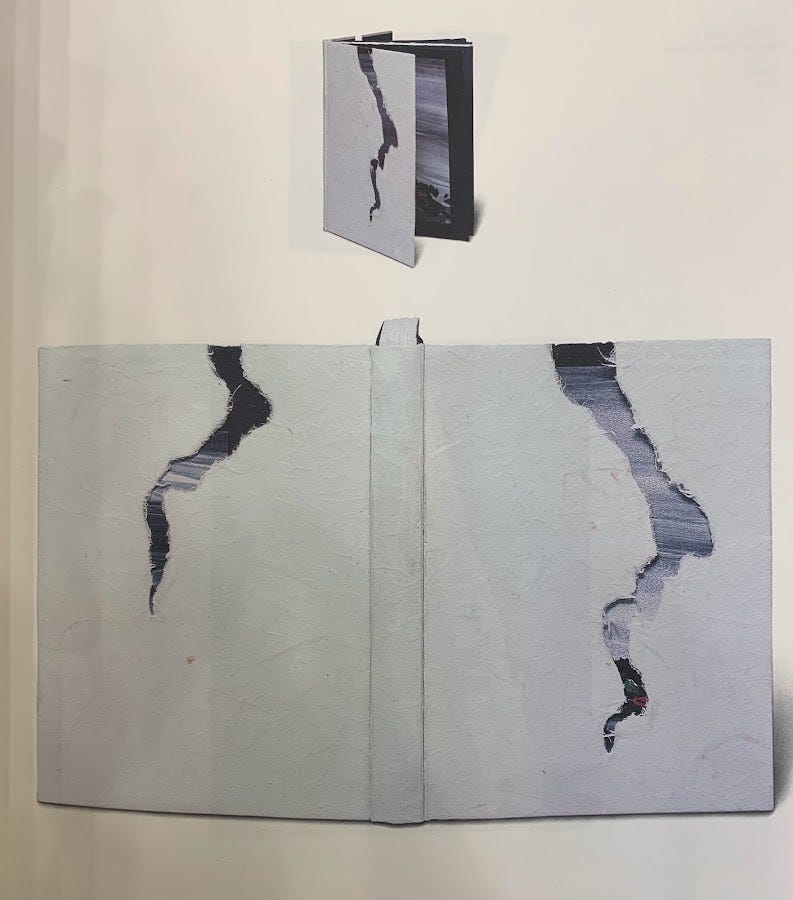

All said and done, you may turn to these books and see a modern celebratory volume and catalog a la many artist books, a subfield of the book world that can be quite difficult to parse without keen interest and experience. I think it’s often easier for rare book practitioners to tell the stories of older objects, because age alone places us in proximity to production processes different than those we employ today. Those processes can be conversation fodder enough. But even bindings in Maestri, many of which are made from unconventional materials, draw from and build on those well-established practices. Take these dos-a-dos bindings, for example:

I was drawn to these books because I like that they demonstrate the links between how we used to make books and how we make them now: techniques aside, each of these bindings required people. The commissioners of this project drew on some serious resources—the directories of professional bookbinding organizations, for example—to pull this off, and they relied on thousands of people, working in their own spaces and in their own time, to get the job done. Besides the named contributors, we must consider the research and studio assistants, editors and literary agents, commissioners and subscribers who helped produce the individual works that comprise the whole. This nearly 600-page catalog documents an enormous exhibition. But it also points to how books are always peopled and placed. To gather all of those expressions in one volume is a profound feat of ingenuity, engineering, and collaboration, as book making has always been.

Housekeeping and birdseeking

house

What I read this week: I reread Beach Read because my cousin emailed to tell me she had read and enjoyed it on my recommendation and I needed a soft pillow for my brain.

What I’m currently reading: The Camp Books Manifesto, which arrived as a fun surprise along with the prints I ordered and that now I’ve stuck to my living room wall.

bird

Binding of L’Infinito by Mayayo Formiga Pablo of Colombia entitled “El Arte en nel Libro” [sic].

More later.

Conway’s copy of L’Infinito is bound in quarter blue morroco and blue cloth boards, with a gray paper spine label, blue endpapers, and a brown paper dustjacket. Maestri rilegatori is bound in full blue morroco, decorated with silver tooling, black morocco and blue and silver calf circular insets, with gray and blue paper spine label printed in blue ink, blue and turquoise speckled pastedowns, and gray hand-made endpapers. Both books have sanded graphite edges.

Ken Liu, the translator of The Three Body Problem by Liu Cixin, has spoken about this extensively, including in this brief interview with Wired.

Are dos-a-dos books typically multi-volume sets?