Tomorrow marks the end of my two-week summer intensive that’s-actually-in-the-Spring on Rare Book Curatorship, a class about why, how, and what people collect, the ethics and possibilities of curation, and the state of the antiquarian book world from the perspective of collectors, librarians, and booksellers. As you might expect, I have enjoyed this class. I wrote my undergraduate thesis about the curatorial theories that built the collection I worked with for two years (a collection of American poetry and plays, which is a fraught premise, but we’ll get to that). I am fascinated by why and how people make decisions of what to keep and not keep, and I am particularly interested in the stories that emerge from amassed materials. One book alone might tell you only a little about someone’s taste, but place it among others that were selected with deliberation and diligence, and much is revealed.

I spent these past two weeks thinking about collecting in all of its facets, assisted by John Carter’s Taste and Technique of Book Collecting, a book first published in 1948 that predicted many of the current trends in book collecting (for example: fewer people care about the “points” of first editions, i.e. the features or typos that distinguish earlier editions from later ones; people are way more interested in previous ownership and marginalia than they were decades ago). Carter emphasizes that to understand book collecting, one must understand the history, priorities, and trends of book collectors, book sellers, and librarians (he also throws in bibliographers, but I’m going to set them aside for now. Sorry, bibliographers everywhere).

Institutional collections, after all, are more a reflection of our predecessors’ interests and priorities than our own; though curators now actively reflect changing tides of whose work should be saved, studied, and taught, the reverberations of those decisions will be felt many years from now, just as we are currently emerging from the shadows cast by the giant halo atop “Western Canon” (whatever the heck that is).

I’m going to dedicate the next few weeks reflecting on the conversations we’ve had in class about book collectors, booksellers, and librarians. Trying to talk about private collecting and institutional collecting and bookselling in just one issue felt like too much. Tonight is about private collecting, the methods and motivations of private collecting, and the opportunity of change.

nothing, nothing at all!

To many people’s confusion, I don’t collect any books myself. I have aggregations of things that are not books: various wind-up music boxes gifted to me by various people (Grandma Phyllis gave me a porcelain Geisha figurine music; my father gave me a saxophone player playing in the French Quarter of New Orleans, his favorite city; my best friend gave me one that plays Clair de Lune). I have Spanish porcelain figurines of women in country dress, a gift from my mother from her father, my abuelo. I have a shelf worth of…porcelain dolls, all gifts from either of my grandmothers from their travels around the world. Now that I list this out, I realize there’s a surplus of porcelain in my room. Not sure what’s up with that.

But none of these aggregations resulted from active intention. And I definitely don’t have an intentional book collection of any kind; the closest is a series of botanical prints that were, again, a gift from a colleague.

I have not yet been compelled to collect books. Carter says that yearning to collect is a crucial component to this hobby. If you’re not motivated (or even feel obligated) to seek things out, wrestle with an absence of information, determine selection criteria and stick with it, then collecting likely will not appeal to you, nor will it be any fun. Collecting shares with curation the principles of selection, description, and interpretation: what am I going to pick, how will I talk about it, and why is it important? I have not yet answered the first question for any one collecting area.

Not that there’s a lack of models to follow. An old-school style of collecting is buying up high spots: books with well-established notoriety, or known and affirmed cultural significance (taught in schools, won awards, subject of research, etc.). Think Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book or like, any Virginia Woolf novel. Carter argues that this kind of collecting is a bit passive: there’s not much innovation in collecting things that other people have already told you are important. It’s much harder to find copies of books in underappreciated, ignored, or outright reviled genres. Rare book dealers likely don’t carry books that don’t already register on the scale of cultural significance (can you see a problem there?), nor might they take new subjects seriously if its not something that is important to them (the whims of subjectivity abound).

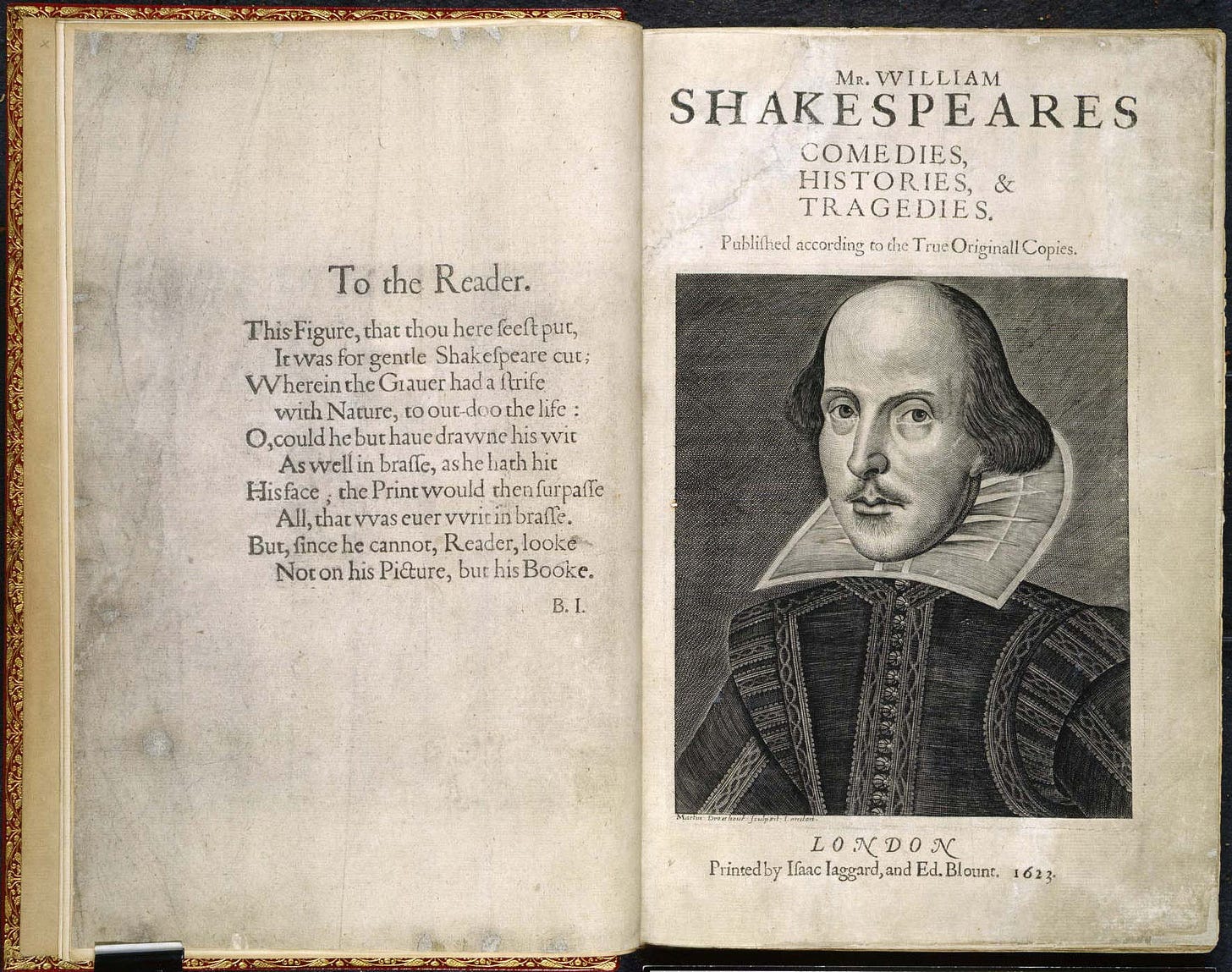

High-spot collecting is a kind of list collecting, or taking a list of books (made by someone else or yourself) and checking all the items off of it. You may recall the Grolier Hundo, the “One Hundred Books Famous in English Literature,” the release of which created an artificial scarcity because suddenly all the moneyed men wanted to buy up the books on that list. That kind of list collecting is kind of like the bridge question: “If all your friends bought a First Folio, would you also buy a First Folio?” “But Mom!”

List collecting can be really useful, however, as a way of identifying every book in a given field, especially for new areas that might not have singular, comprehensive checklists of everything printed in that genre.

Such is the case of rare romance collectors, champions of a long-discounted genre that is increasingly gaining attention from booksellers and (very) slowly gaining institutional traction. Jessica Kahan won the inaugural Honey & Wax Collecting Prize, a prize that promotes book collecting among American women 30 and younger, with her extensive collection of rare romance novels. Kahan collects according to strict criteria: she only buys first edition hardcover volumes of 1920s and 1930s romance novels in their dustjackets (and the dustjacket has got to be good). Her collection has grown so large that it’s now increasingly expensive to complete as she comes down to the last handful of books (this is known as gap-filling, or finding the missing pieces).

Kahan also exemplifies how private collectors often become experts and educate dealers or institutions on the value and extent of their subject area: she created her own bibliography of Jazz Age romance novels, the likes of which did not exist until she sat down and compiled all of the known sources (as well as ones she discovered herself). She is in good company: Caroline F. Schimmel, a famous collector of fiction of women in the American wilderness, actively taught dealers about the presence of women in their stock as she accrued over 25,000 volumes, 6,000 of which now live at the University of Pennsylvania. She wrote a book about her collection called OK, I’ll Do It Myself, which is the five-word summary of this issue.1

This degree of specialized knowledge can ultimately influence institutional collections; private collectors have significantly more leeway in carving out new areas to find books, even if they are constrained by limited funds (not all collectors are uber wealthy, even though book collecting has long been a service industry catering to the literary tastes of wealthy white men). It would be somewhat straightforward for me to wake up tomorrow and say, “I’m going to collect zines relating to Black-Jewish solidarity in protest movements” and jumpstart my collection buy purchasing a few items. To begin collecting those works institutionally, a librarian would likely have to get permission from at least one staff member with purchasing power (a curator or director, perhaps), register the bookseller as an approved vendor, then fill out a purchase order and get the University to pay from the library’s endowment or budget. And that’s assuming the librarian has curatorial power or suggestion privileges at all, and that the acquisitions budget isn’t tied to specific requirements dedicated to collecting materials related only to cats or whales or industrial logging.

I don’t enumerate these steps to dunk on academic librarians, I do so to illustrate how much more flexibility an individual collector has to build a robust collection and one that might find itself in a library down the line. Last week, I live-tweeted a panel of previous winners of the Honey & Wax Collecting Prize, and they each discussed the constraints they face in collecting niche areas, often having to look in creative, community-based markets for their materials. Jessica Jordan collects art by Leon and Diane Dillon, two trade artists who have designed hundreds of book and magazines covers, and she finds many of her books at library and used bookshop sales. Emily Forster collects fan-made publications and purchases them almost exclusively online and, in the Before Times, at conventions. And Miriam Borden collects Yiddish language-learning materials, which she acquires through word-of-mouth and donations from shuttered Yiddish-language teaching centers.

Even still, each of their collections argue that carving out niche areas can be extraordinarily fulfilling. And their collections inch book collecting away from simply nabbing first editions or association copies or big-name writers (though people will always be interested in those approaches). The future preservation of these new compulsions is unclear, but if these collections donate or sell their collections to institutions, they will contribute to broadening curation on a systematic level.

housekeeping and birdseeing

house

If you’re interested in learning a bit more about the private collectors I mentioned, you can read about them and their essays on the Honey & Wax Prize webpage.

If you’re interested in listening to a really knowledgeable person talk about romance novels, Rebecca Romney of Type Punch Matrix recently visited the romance podcast Shelf Love and talked about collecting rare romance novels. It was a great episode!

What I read this week: Taste & Technique in Book Collecting by John Carter; Dr. Rosenbach and Mr. Lilly by Joel Silver; and The Midnight Library by Matt Haig (3 stars, too predictable)

What I’m currently reading: Typical American by Gish Jen and Libertie by Kaitlyn Greenidge, for (you guessed it!) Roxane Gay’s book club.

bird

The Mourning Dove chicks hatched! I only caught a glimpse of them sticking out over the nest, but last Tuesday I watched the parents give the chicks flying lessons from the trellis to the ground. It was mesmerizing. After Tuesday, they began taking longer breaks from the nest, and by Thursday they had left. I will miss them! What a special way to usher in the new season. I am one hundred years old inside.

The finches are now highlighter yellow.

More later.

(Schimmel is also featured in the documentary The Booksellers, which I will talk about in a later part of this series. The point here is that collectors in unique areas often and necessarily become experts in those areas.)